A Learning on Alerting: How We Started Fixing Our Not Great Alert Situation

It was a real Journey to the Centre of Our Alerting

16 Jan 2025Throughout my time at my current gig, I have had an ongoing nemesis - alerting. For the longest time, my team has been besieged by an overwhelming amount of alerts. Recently, the opportunity finally arose for us to be able to deal with them, and I thought it’d be good to document how we’ve started our journey in getting our alerting back into a healthy place.

Setting the scene

Before we get into the wider story, I thought it would be good to provide a bit of context into what I work on. My team is currently building a Kubernetes based platform. It currently helps support the traffic routing throughout the company, and we’re in the early stages of workload migration to it.

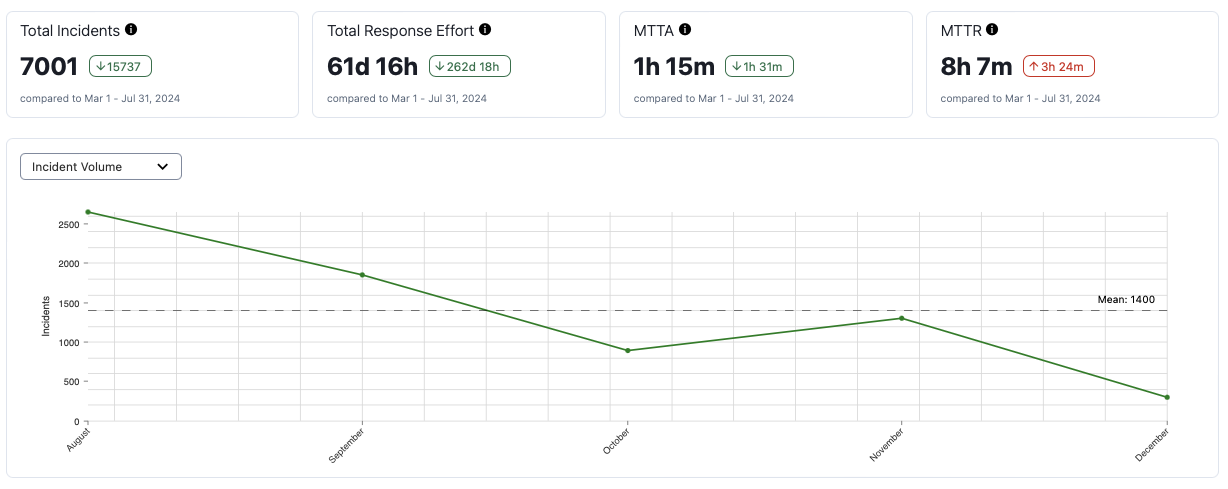

As I said before, we’ve been dealing with high number of environments for at least over a year. To put some numbers to it, for the entire month of August, we had 2653 incidents in PagerDuty. Majority of these were marked as low urgency, which meant they were self resolving and didn’t ping us, so thankfully we weren’t being actively interrupted but it did weigh down on us in other ways. The sheer volume of alerts was overwhelming and created a high noise to signal ratio. It manifested as over 4700 automated Slack messages per month across our alert channels, so even if there was constructive conversations happening, trying to find it was like finding a needle in a haystack.

What was actually wrong?

We weren’t blind about the problem. We all recognised that the amount of alerts were an issue, and that we wanted to fix it. However, for one reason or another, there was always a more pressing issue that needed to be addressed.

Even if we did have capacity, another dilemma we faced was that we didn’t know how many of these alerts were actually useful or provided value. A lot of the alerting had been set up by previous iterations of the team and the reasoning behind them had been lost. We didn’t want to delete alerts in case they were valid and legitimately required fixing.

Faced with both of these problems, we fell into complete alert fatigue and apathy, accepting the noise as something we lived with. Our saving grace was that we were confident about the state of our production alerting - we had a high first notification rate for any major incidents so we felt comfortable that we weren’t missing any P1s or anything. However, I’m starting to think that was just survivorship bias and we were missing other important problems but felt like we weren’t.

In August, we finally had some time and capacity to deal with the alert situation. We just needed to figure out how we wanted to go about it.

First steps to fixing alerting

When we started out work, we thought it would be best to try and get some immediate wins. We had the assumption that even if we weren’t sure if we needed an alert, we would at least be able to fix it from firing often. So the team identified the top 10 firing alerts and created cards to deal with them. The cards were simple in scope: look at why the alert was firing, determine what the best action to resolve it is, and then resolve it.

An example of one the cards used for investigating an alert. We love a tightly scoped card 👏

An example of one the cards used for investigating an alert. We love a tightly scoped card 👏

After the first top 10 alerts were dealt with, we identified the next top 10 alerts and repeated the process. We did this until all the low hanging fruit had been fixed. It was the quick win we needed, after doing it a couple times we went from ~730 alerts per week down to ~170. Still not great but we could at least look at our alerting a bit more critically.

A philosophical approach

So now that the noise was quieter, we had time to tackle the deeper issue. The team knew that our alerting approach needed improving, but we didn’t know what our ideal alerting setup even looked like - stuff like what we wanted to alert on, when they should fire etc. We all had our own thoughts but we needed to be aligned before we tried any further improvements.

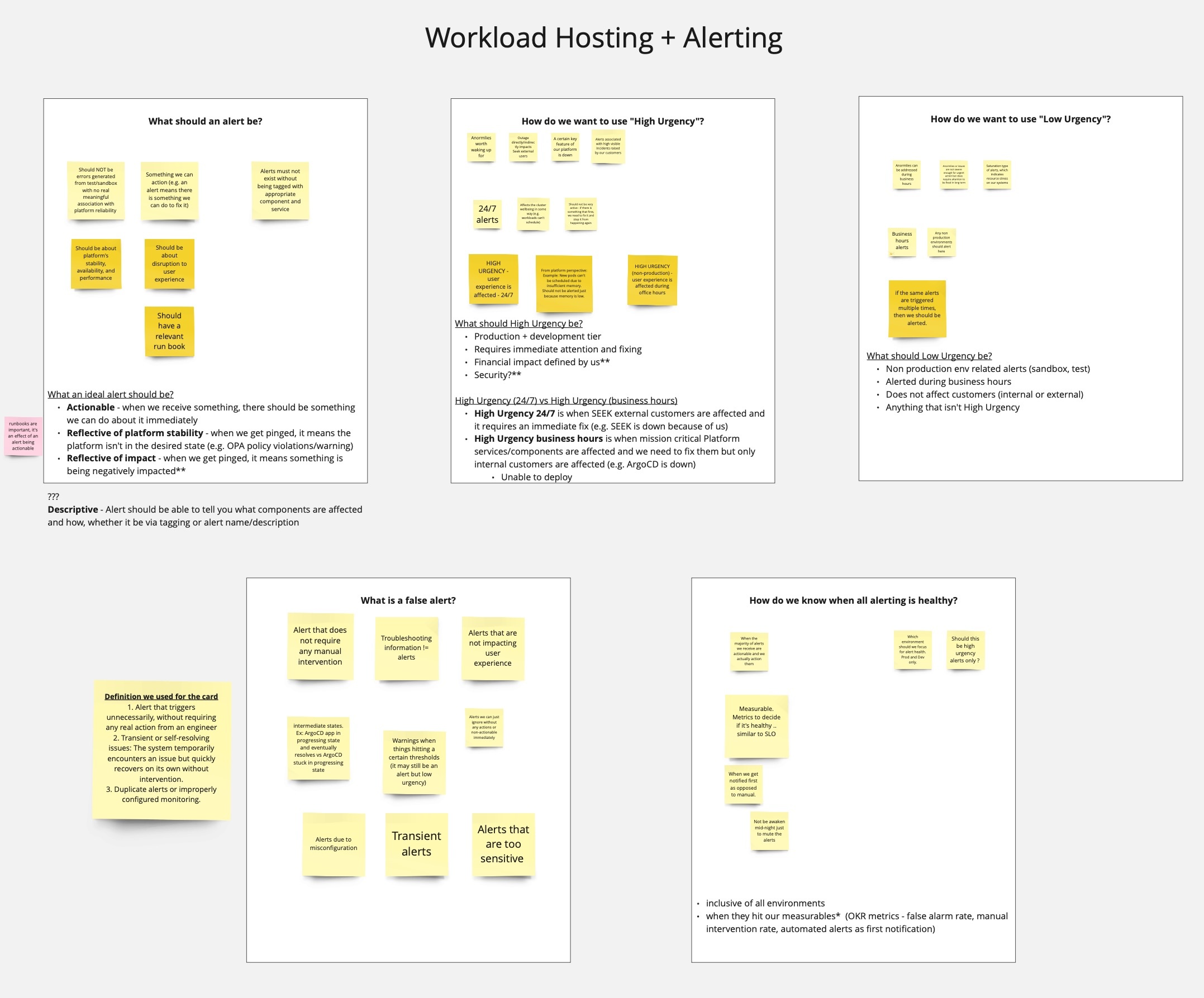

To fix this, we decided to run a quick internal workshop where we all talked about what we think our alerting should look like, based on some simple pre-organised prompts. We were actually pretty in line with each other so there wasn’t much disagreement, which was nice. From the answers we got from that workshop, we then created the document which we call our alerting philosophy.

Here’s what the end of our workshop looked like. We all placed our answers as sticky notes on the key questions, discussed then afterwards summarised our final thoughts.

Here’s what the end of our workshop looked like. We all placed our answers as sticky notes on the key questions, discussed then afterwards summarised our final thoughts.

But what is an alerting philosophy?

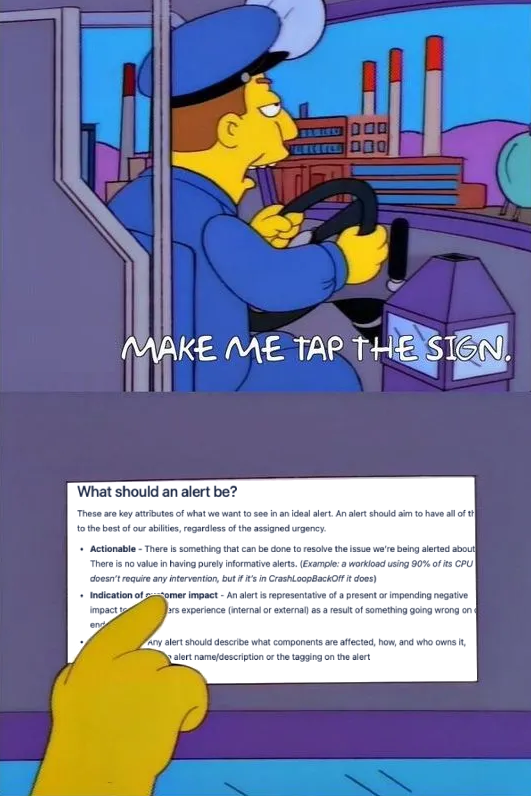

The alerting philosophy is like a mission statement, outlining everything we want to our alerting to be. We’ve tried to make it as succinct and easy to reference as possible. I am personally a big fan of having a “sign to point to”, documentation that we can easily reference which provides clear answers to whatever questions are asked.

Me every time I get to reference a “sign doc”

Me every time I get to reference a “sign doc”

The document answers four key questions, which I’ll go over and briefly touch on some of the beliefs we follow

What does the ideal alert look like?

The ideal alert should be:

- actionable: something can be done to fix the alert when I am paged

- representative of customer impact: only alert when there’s something going wrong which will affect customers (internal or external)

- descriptive: alert tells me who and what is impacted, and how

What is the difference between High Urgency and Low Urgency alerts?

High Urgency is used for all production environments and will page us 24/7. When we get a High Urgency alert, it’s a “drop everything” immediate priority to fix. Low Urgency is the inverse: used for non-prod environments, only pages us during business hours or not at all, should be actioned ASAP but no need to stop something else to do it.

What is a false alarm?

A false alarm is any alarm that’s transient in nature, or does not require (nor will it ever) manual intervention to resolve.

How do we know when our alerting is healthy?

We need to monitor key alerting metrics (% of alerts that pages the team , false alarm rate, Time to Respond etc.), and measure them against achievable thresholds. If they’re all good, alerting is healthy.

In my opinion, alert fatigue is something important to consider when it comes to alert health too. Right now it feels like more of a vibe check to me than a measurable metric, but I’m sure there’s going to be a correlation between the metrics a team chooses to measure for alert health and the feeling of alert fatigue.

How do we use this philosophy?

We use it as our guiding light for all ongoing and future alerting work. When we do our weekly review of all the alerts that have fired, we reference our definition of false alarm to make sure we’re correctly measuring what are real alerts and what aren’t. As we continue to review existing and even add new alerts, we make sure that they meet the standards outlined in our philosophy. It will also be really great for us as we grow our team and platform - we can point at the sign and say “this is what we aspire to” and all newcomers will be able to immediately get up to speed.

It’s worth noting that like all documentation, the philosophy is alive and will likely change. What we need right now will probably change, especially as our platform grows. As much as we use it to guide us, we will also need to review it and make sure it is still effective!

So what’s it like right now, and what’s next?

Right now, things are going a lot better than they were when we started our work. In the month of December, we had 298 alerts. That’s a nearly 90% decrease in alerts! It’s still too high and it’s got a high false alarm ratio, but I’m proud of the progress we’ve made. Like I said, this is the start of us fixing our alerting.

Alert graph straight from PagerDuty, for the period of August to December

Alert graph straight from PagerDuty, for the period of August to December

As for what’s next: In the immediate future, we’re splitting up alerts to be more service specific which is giving us a chance to review what we’ve got and what we need. Through this work I’m expecting that we’ll be able to slowly but surely ensure that all alerting owned by our team matches up to the philosophy doc that we’ve got. This alongside weekly reviews of our alerts will help get that alert count even lower.

In the long term though, I’d expect us to come back to the alerting philosophy (and by extension our alerts in general) after wider adoption of our platform and change things up in reaction to new challenges we’ve faced. Maybe it’ll have harder rules about being representative of customer impact, maybe we’ll think we’re too lenient and should have more high urgency stuff. Who knows? The only thing I definitely don’t want to see in the future is 2000+ monthly alerts. I have seen what the light looks like and I never want to go back.